Multi-Myosharp

Overview:

Electromyography (EMG) is the most popular way of controlling modern upper-limb prostheses. This is often done by placing EMG sensors on the surface of the residual limb. Measured signals are then processed and eventually converted to a desired motion of the prosthesis. EMG signals are notoriously hard to decipher consistently, prone to interfering noise and heavy reliance on “ideal” conditions. EMG systems vary drastically in quality with an accompanying price tag. Single sensors can be purchased by hobbyists from as low as 50 CAD, while more complex systems targeted at cutting-edge researchers can rise to well over 20,000 CAD. Many researchers use a popular and cheap system called the Myo Armband, which sold for around 200 CAD. The Myo Armband was targeted at a more general audience for interfacing with common computer programs; however, it ended up making its way into many prosthetic research labs. Sadly, the device has been discontinued, though CTRL-Labs just bought the IP, and it looks like they will have a new-and-improved Myo Armband out soon.

In the BLINC Lab, we mainly use C# GUI’s to interface with our robotic equipment and use the Myosharp library to interface with our Myo’s. I made a few minor additions to this library to work with newer versions of visual studio, handle multiple Myo’s simultaneously, and improve data acquisition consistency. The forked repo is on my Github.

Visual Studio 2019 Compatibility

Myosharp relied on a certain variant of Code Contracts that is no longer supported in newer visual studio versions. Luckily the non-supported assembly was only used for bug-avoidance purposes and did not affect the actual functionality. I removed all of the code contracts-related items, and myosharp now compiles in visual studio 2019.

Multiple Myo Reading

Recently I found myself in need of measuring signals from many Myo Armbands simultaneously. This required some overhead to keep track of various Myo IDs to ensure data was kept separate for each connected Myo. I wrote this functionality into a class in the Myosharp namespace titled MultiMyoManager. Though I have only tested the class with two myo’s, it should work for as many as desired.

Inconsistent Data Acquisition

I noticed many duplicate values in the logged data when using Myosharp, even when sampling below 200 Hz (the Myo EMG sample rate). Sometimes duplicate values would occur 6-7 times in a row, which shouldn’t happen with a time-varying EMG signal. I placed a file writer directly in the Myo data acquisition event function to log the time data was received.

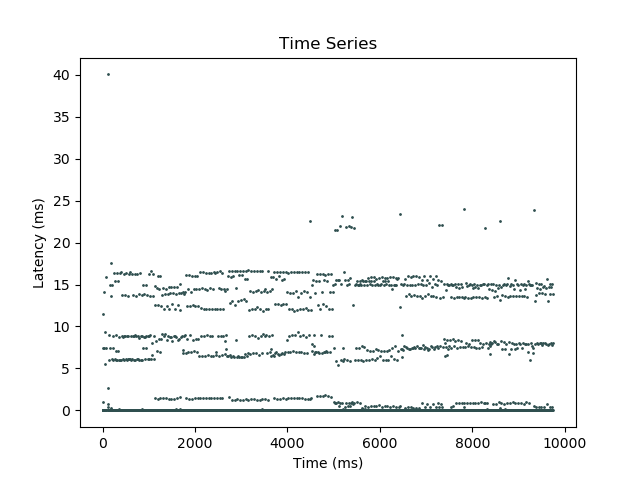

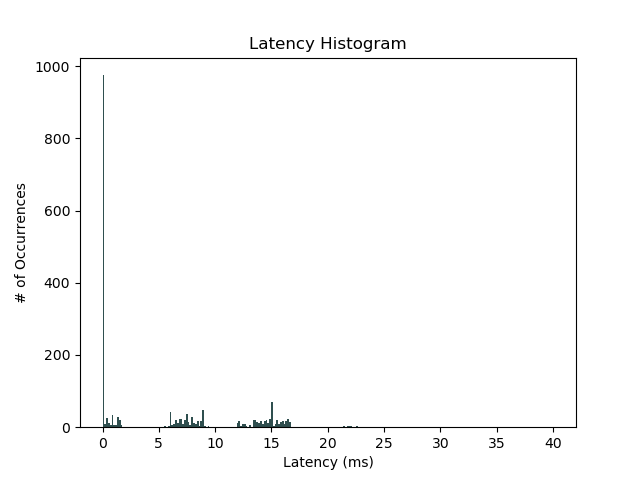

Notice how stratified the time series latency is. Looking at this histogram, most of the transfers occur between 0 and 1ms. I expected to see all of the transfers centred over 5ms, as this is the stated sample rate of the Myo device. In fact, the average latency is exactly 5ms.

It seems that most events happen in rapid succession, followed by longer delays. The duplicate logged values I was seeing were likely due to some form of buffering issue in Myosharp. Many data packets build up and are all released at once. This buffer/release format is an issue for our real-time robotic control interface since it grabs values at fixed intervals. Say Myosharp sends ten packets in rapid succession, each packet overwrites the previous packet, and only the last packet is available to our application. If Myosharp then delays 50ms (since it just sent 50ms worth of data packets), for those 50ms, our application will repeatedly read the last value.

By keeping a history of data values sent, this problem can be mitigated. I implemented a queue (First In First Out, e.g., a lineup at a movie) data structure into the MultiMyoManager class. Each time an EMG data acquired event is triggered, the oldest value in each queue is removed, and the newest is added. This way, when Myosharp dumps a bunch of data packets simultaneously, the queue shifts correspondingly. The queue is read at a fixed, known time interval to get the current real-time data. A separate index variable keeps track of where in the queue we are currently reading from. Each time it reads a value, it increments the index variable forward in the queue to point to the next newest value. Simultaneously, each time a new data packet is added to the queue, this index variable shifts backward to account for the queue shifting.

Results:

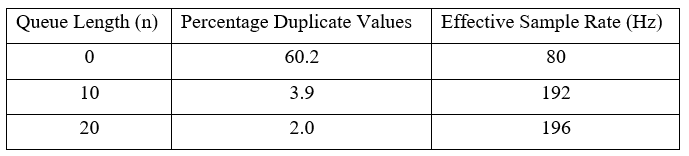

Here is a table comparing the number of duplicated values before and after implementing the queue system while reading data at 200Hz.

The queue is working as anticipated. I left a queue length of 10 in for the time being to reduce computational overhead.

Notes:

Unless the fixed real-time reading rate is identical to the EMG event triggering rate, the queue index will eventually shift to one of the queue’s ends. E.g., if the fixed reading rate is slightly faster than the EMG event rate, the index will eventually migrate to the front of the queue, and duplicate values can again occur. However, this will still protect against large data packet dumps. Another issue is this adds a potential delay. E.g., if the fixed reading rate is slightly lower than the EMG event rate, the index will eventually migrate to the back of the queue. Reading from the back of the queue means that we will always have a delay time of 5ms times the queue’s length. Although the previously described problem reads duplicate values, it is guaranteed to have the newest data packet.