Force Myography

Overview:

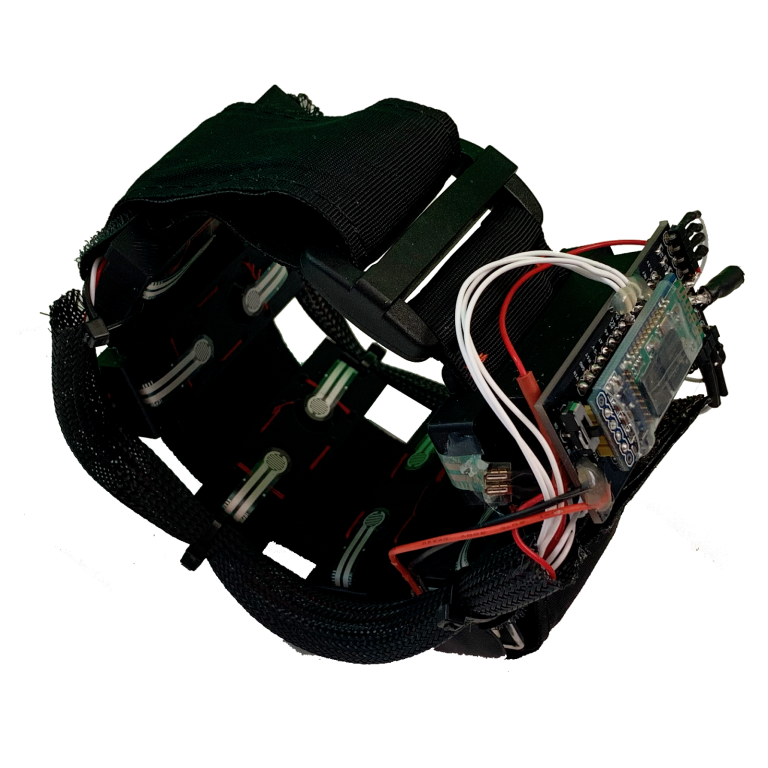

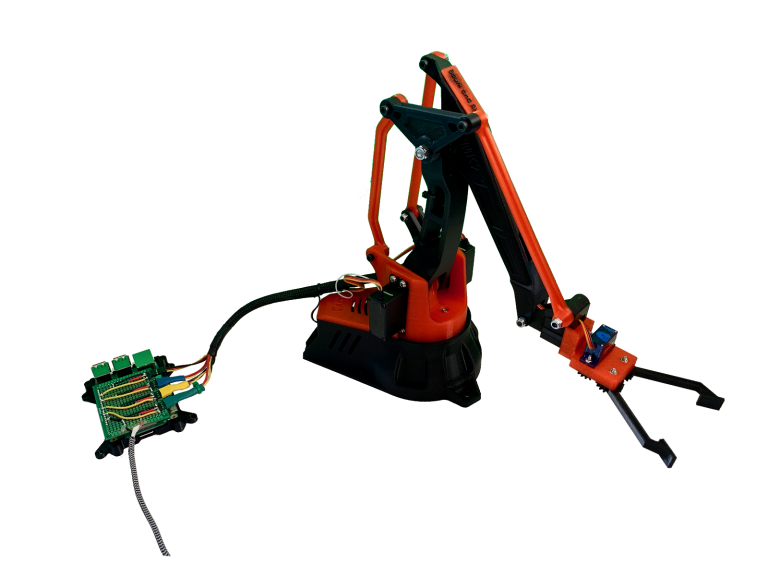

My friend Mark Sherstan and I started this project as an entry to the 2019 HACKED hackathon hosted at the University of Alberta, where we placed 2nd out of 300+ teams. The initial prototype wasn’t very refined due to the competition’s 24-hour time limit, so we made a second version as part of a class project (MecE 653, Signal Processing). The result was a low-profile wristband containing 11 force-sensitive resistors and an inertial measurement unit capable of sampling reliably at 200 Hz. We have achieved classification accuracy much higher than typical EMG results on over eight different hand classifications. We also demonstrated that this device could control multiple degrees of freedom simultaneously on a simulated prosthesis in real-time. This is a step towards a more reliable control interface for commercial prosthesis devices. A brief overview of the motivation and implementation is given in the video to the right. For a more comprehensive overview of the system, check out our final report focusing on the design’s signal processing aspect. All of the code is available on our GitHub repository.

Motivation:

Although many multifunctional hands are available for prosthesis use, commercial devices cannot utilize them largely due to restricted control interfaces. Recent research has focused on improving pattern recognition algorithms to decode electromyographic signals (EMG) into multi-degree freedom movements to enable more robust control. Although results are promising in laboratory conditions, this technique cannot be transferred into commercial devices. This is largely due to current surface mounted EMG sensors having inherent unpredictable issues that affect the algorithm’s performance, such as cross-talk, electrical interference, muscle fatigue effects, perspiration effects, and skin impedance. An alternative to this technology for use in prosthetics is force myography (FMG). This technology seeks to exploit the deformation resulting from residual muscle movement to obtain prosthesis control. This is typically done in a very similar manner to EMG; however, instead of measuring electrical activity, an array of pressure sensors wrapped around the user’s arm measures muscle deformation. The measured sensor values act as inputs into a pattern recognition algorithm to predict the user’s desired motions.

Hardware:

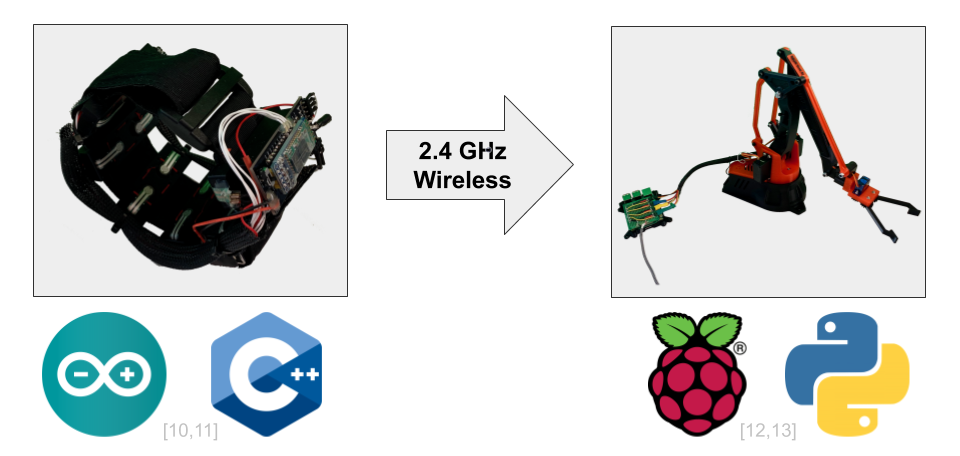

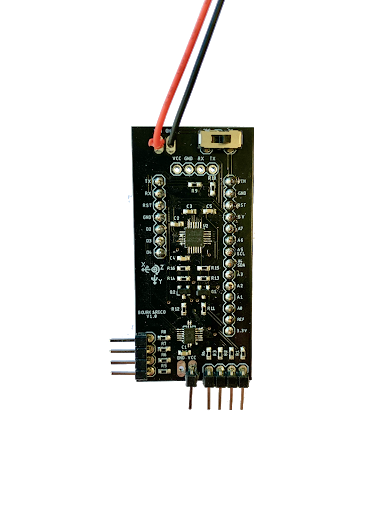

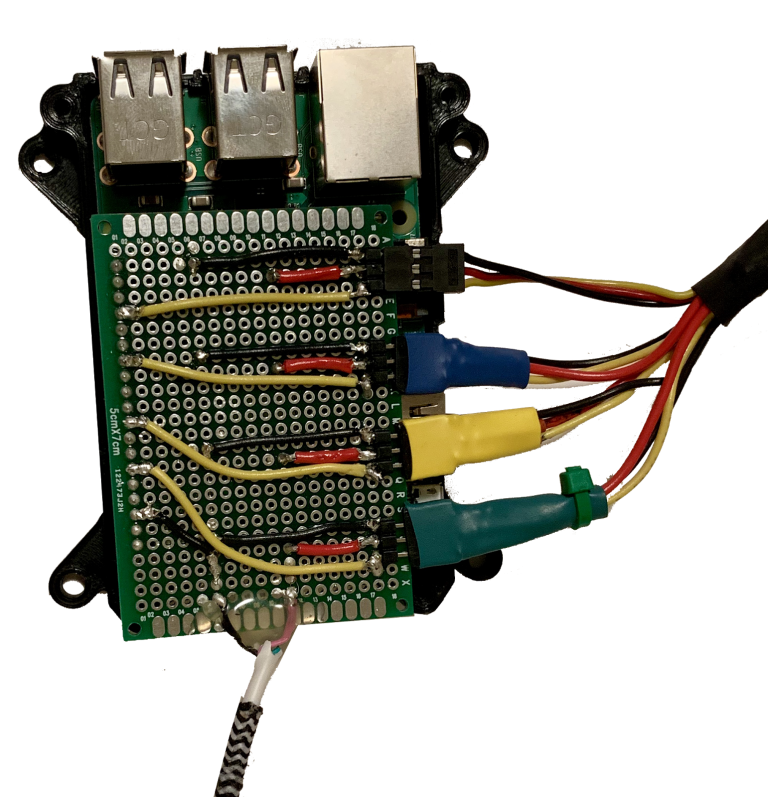

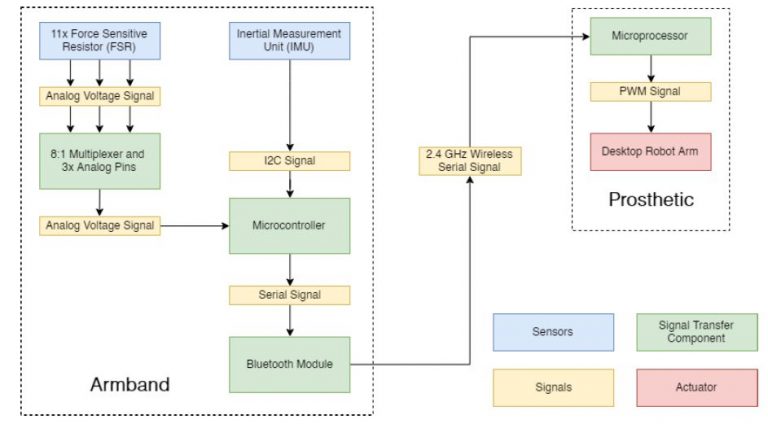

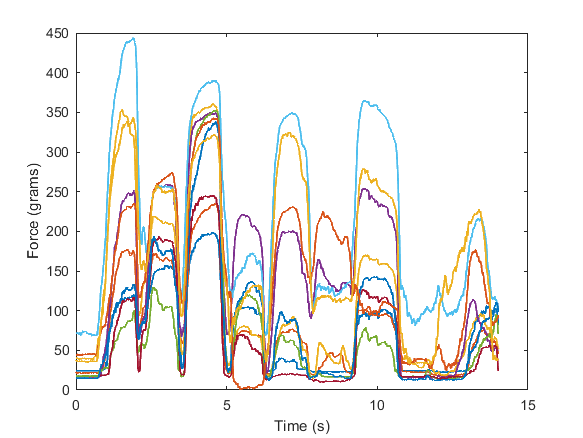

A low-profile variable-sized armband was designed and manufactured to measure the force created by musculotendinous changes in the forearm and the arm’s orientation and movement. The armband includes a custom-designed printed circuit board (PCB) which interfaces with eleven force-sensitive resistors (FSR), an inertial measurement unit (IMU), a microcontroller, and a Bluetooth module. The armband wirelessly sends raw sensor values to a microprocessor where all computation occurs, such as digital signal processing, pattern recognition, and real-time control of a desktop mounted prosthetic arm.

Classification:

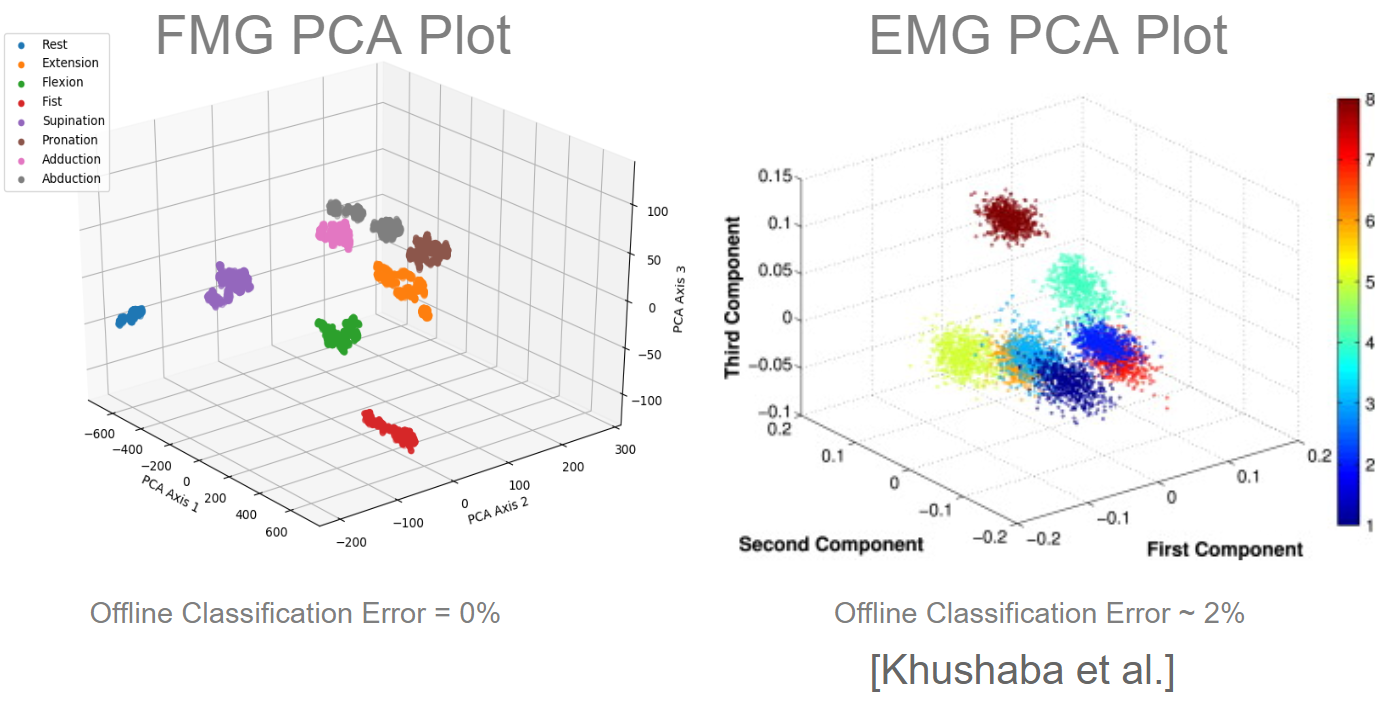

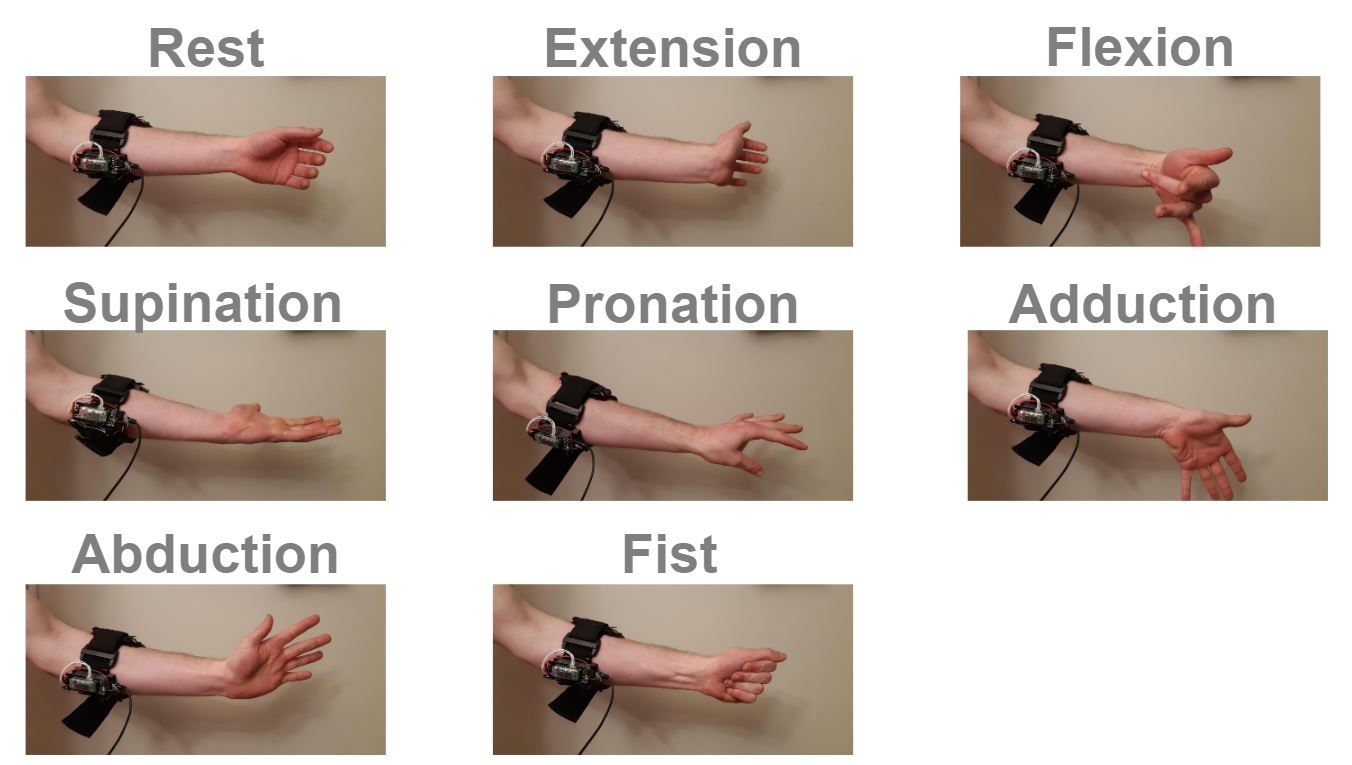

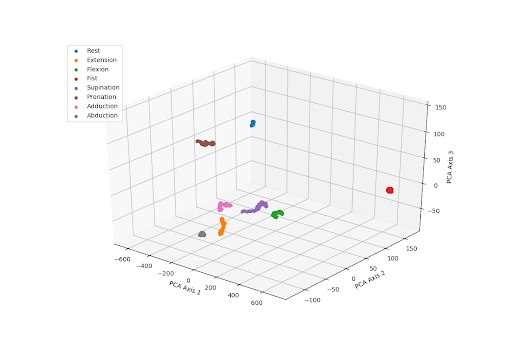

8 different hand gestured were used to train a support vector machine classification algorithm. No feature engineering was done. 100% Accuracy achieved with about 200 points of training data for each class (80/20 training vs. testing split). Using principal component analysis to squish the data down to 3 dimensions, high separability between classes is seen.

Comparison to EMG:

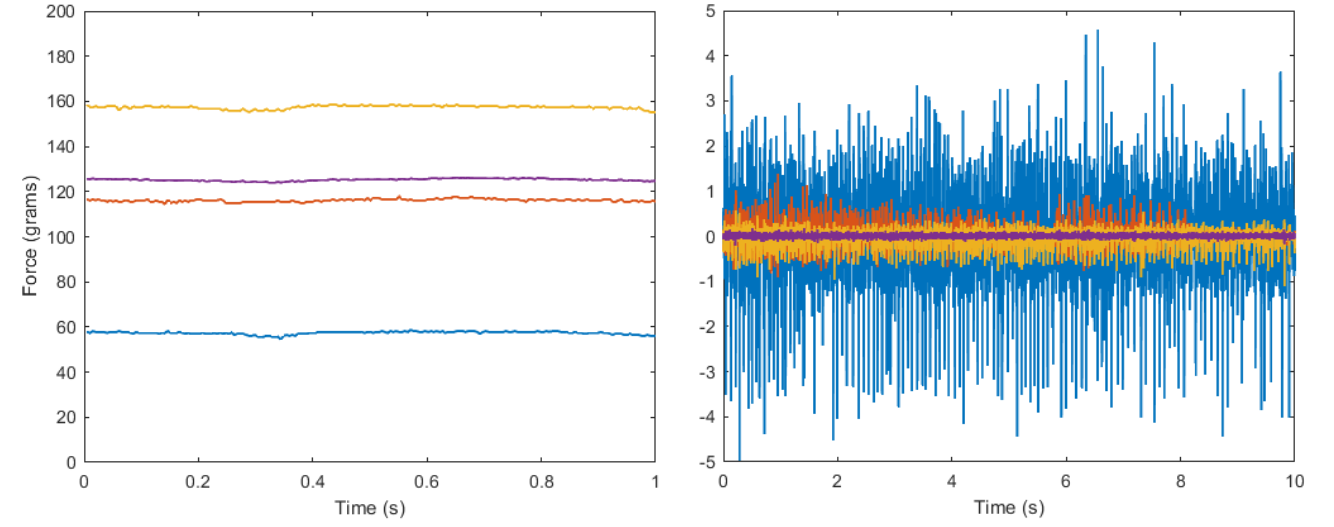

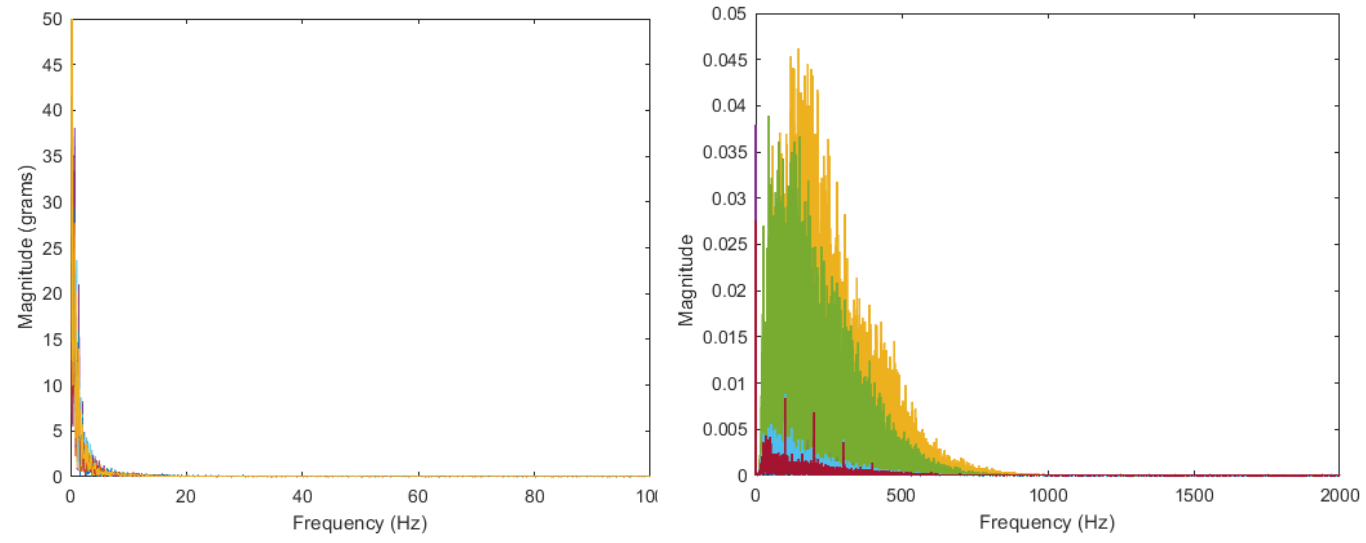

Each FSR cost is around $10, whereas EMG electrodes can be upwards of $1000. This is because the signal processing required to read the tiny voltage signals inside the muscles from the skin’s surface is quite difficult. The EMG signal is inherently oscillatory even when muscles hold a contraction, with the useful frequency range being between 10-250 Hz. To use this frequency range, a high sample rate >500Hz is required. FMG signals, on the other hand, are not time-varying under constant muscle contraction, making the signal much easier to interpret. Feature extraction techniques are mandatory when using pattern recognition techniques with EMG due to the sinusoidal signals. Window sizes of 250ms are typically used to calculate input features. Feature sets previously investigated include time-domain (mean absolute value, zero crossings, etc.), frequency domain, wavelet, and many more. On the other hand, no feature extraction is necessary with FMG signals. Classification accuracy for FMG is typically reported as higher than EMG. For both EMG and FMG, classifier choice has little impact on accuracy. To visualize separability, an open-source EMG dataset with similar gesture classifications was compared.

EMG comparison data obtained from:

R. N. Khushaba, Maen Takruri, Jaime Valls Miro, and Sarath Kodagoda, “Towards limb position invariant myoelectric pattern recognition using time-dependent spectral features,” Neural Networks, vol. 55, pp. 42-58, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2014.03.010